OpenStreetMap User's Diaries

Sap

Sapp

Sapp

Sapp

Sapp

OpenStreetMap Blogs

OpenStreetMap BlogsSapp

Sapp

After 3+ weeks of silence following the RFC discussion (no further comments/objections), the proposal is now officially in Voting Phase!

📋 Wiki: osm.wiki/Proposal:Civil_Protection_Areas

🗳️ Vote until: March 23, 2026

🖼️ Live demo: andreadp271.github.io/civil_protection_areas_osm/

Key improvements from RFC feedback:

After 3+ weeks of silence following the RFC discussion (no further comments/objections), the proposal is now officially in Voting Phase!

📋 Wiki: osm.wiki/Proposal:Civil_Protection_Areas

🗳️ Vote until: March 23, 2026

🖼️ Live demo: https://andreadp271.github.io/civil_protection_areas_osm/

Key improvements from RFC feedback:

Comparison tables vs assembly_point/disaster_help_point

Clear shelter area distinctions (outdoor vs indoor)

Refined rescue staging/logistics definitions

| Please cast your {{vote | yes}}, {{vote | no}} or {{vote | abstain}} on the Wiki! |

標高といえば、一般的に山頂の高さをイメージすると思う。

あとは水準点、基準点とか…

なので、eleを日常的に入力する機会は多くないかもしれない。

OSM wiki

入力したことないって人も多いだろうが、意外と標高は身近なところで表示されている。

それは…

♦

国土交通省が東日本大震災による津波被害を踏まえ、対策として海抜情報(海抜表示シート)を提供。

街路灯に信号、道路標識などに貼り付けており、海沿いの地域では多く設置されている。

♦

自治体も電柱に貼ってたりする。向きによっては見落としがち。

防災意識の向上、避難の目安として設置しているが、スルーして通り過ぎてませんか?

私は

標高といえば、一般的に山頂の高さをイメージすると思う。

あとは水準点、基準点とか…

なので、eleを日常的に入力する機会は多くないかもしれない。

OSM wiki

入力したことないって人も多いだろうが、意外と標高は身近なところで表示されている。

それは…

国土交通省が東日本大震災による津波被害を踏まえ、対策として海抜情報(海抜表示シート)を提供。

街路灯に信号、道路標識などに貼り付けており、海沿いの地域では多く設置されている。

自治体も電柱に貼ってたりする。向きによっては見落としがち。

防災意識の向上、避難の目安として設置しているが、スルーして通り過ぎてませんか?

私はマッピングするまで、まともに見たことありませんでした…

探すつもりがないときによく見かけ、いざ探すとなかなか見つからない…

学校、公民館などの指定緊急避難場所に設置されている。

あと、津波避難ビルや公園の地震時の緊急避難場所の看板にも書いてたりする。

自治体などがオープンで公開しているので狙い撃ちで探せる。

OSMには(少なくとも自分の周りでは)あまり登録されていない印象。

オープンデータからインポートを… ていうのは、いろいろメンドイから割愛。

私は周りのマッピングも兼ねて現地確認してます。

地理院地図ではDEMから取得できるし、等高線という素晴らしい表記方法もある。

なんならマップに描画されないんだから、いるのか?って感じだが、

ピンポイントの数値として残して記録しておくと、

などで役に立つかもしれない。

私にもわからん

調べ方が足りないかもしれないけど、

サンプルがみつからなかったので勝手にいれているが…

ele=3

inscription=ここの地盤は海抜(標高)3m

man_made=sign

本当に申し訳ない

有識者の方々、ご教示ください

見かけはするけど、気にせずそのまま通り過ぎるこの2つ。

防災の意識を見直すついでに、自分が立っている高さ(Z軸・人によってはY軸)にも目を向けてみるのも面白いかもしれない。

Lawa Lawa Luo, Ulugawo Nias

Lawa Lawa Luo, Ulugawo Nias

Mentre scarico alcuni dati dal geoportale della Regione Lombardia, guardo gli ultimi nodi mappati e noto che molti di questi sono defibrillatori.

Ma perché?

Direi che è iniziato per caso, quando ne sono stati aggiunti alcuni nel campus universitario che frequento. Il senso però lo trovo qualche tempo dopo, quando alla festa di laurea di una delle mie migliori amiche la zia della

Mentre scarico alcuni dati dal geoportale della Regione Lombardia, guardo gli ultimi nodi mappati e noto che molti di questi sono defibrillatori.

Ma perché?

Direi che è iniziato per caso, quando ne sono stati aggiunti alcuni nel campus universitario che frequento. Il senso però lo trovo qualche tempo dopo, quando alla festa di laurea di una delle mie migliori amiche la zia della festeggiata - cardiologa - mi fa giustamente notare che durante le emergenze, quando la velocità conta, è meglio sapere dove sono piuttosto che non saperlo affatto.

E questa cosa mi fa riflettere, mi risuona ininterrottamente nella testa, soprattutto se consideriamo l’attività di mapping non solo come “raccolta di dati georiferiti” ma anche come possibilità concreta di migliorare (e talvolta salvare) la vita delle persone intorno a noi.

Da allora, anche aiutandomi con MapComplete che in questo caso mi risulta utilissima, mappo tutti i defibrillatori che mi passano davanti agli occhi. Anche allungando i tempi di viaggio per fermarmi a quella fermata che mai avrei frequentato (dai, chi scende a Caiazzo?), anche per confermare lo stato di quelli esistenti.

Avrà effettivamente dei risvolti positivi sulla vita delle persone? Chi lo sa. Intanto ci proviamo.

Rail trails with route relations with railway=abandoned to denote a rail trail is not working. When the named “bike route” enters city streets or along side walks where the railroad never went this becomes and tagging nightmare.

I have had to remove railway=abandoned from a route relation in British Columbia and in New Hampshire where these were both issues. osm.org/note/5066887#map=15

Rail trails with route relations with railway=abandoned to denote a rail trail is not working. When the named “bike route” enters city streets or along side walks where the railroad never went this becomes and tagging nightmare.

I have had to remove railway=abandoned from a route relation in British Columbia and in New Hampshire where these were both issues. osm.org/note/5066887#map=15/41.40203/-73.62096

osm.org/note/4680502#map=15/49.49511/-121.22581

Can we find a better tags to mark bike routes with rail trail?

this is specific to route relations and not current tags for infrastructure, railway=abandoned still works for infrastructure

I would propose something like railway=trail so we keep this straight. It looks like railtrail=yes is a tag.

Yours in Mapping Natfoot

this is related to my other project on routing and bike routes. ask if you want to know more.

Continue rea

26/02/2026-04/03/2026

[1] | Podoma in action in Italy | map data © OpenStreetMap Contributors.

wetland=tidalflat tag.highway=crossing tags produce near-zero crossing scores, and calls on SE Asia mappers to improve pavement (sidewalk) and crossing tagging.Note:

If you like to see your event here, please put it into the OSM calendar. Only data which is there, will appear in weeklyOSM.

This weeklyOSM was produced by PierZen, Raquel IVIDES DATA, Strubbl, Andrew Davidson, barefootstache, derFred, izen57, s8321414.

We welcome link suggestions for the next issue via this form and look forward to your contributions.

This is not about the Linux Foundations Overture Maps attempt to hoodwink the Open Geospatial Consortium into standardising Overtures GERS (Global Entity Reference System) 1. There is so little technical content available in that proposal that it is difficult to write even a short paragraph about it. But it is motivated by Overtures attempt to engage in the great American tradition of selling sn

This is not about the Linux Foundations Overture Maps attempt to hoodwink the Open Geospatial Consortium into standardising Overtures GERS (Global Entity Reference System) 1. There is so little technical content available in that proposal that it is difficult to write even a short paragraph about it. But it is motivated by Overtures attempt to engage in the great American tradition of selling snake oil by suggesting that GERS solves real problems 2. None of the following is new, and all this has been discussed many times in the OSM community.

It isn’t as if having a persistent id for an entity isn’t useful, for example if you are running a restaurant review site3 you definitely want a way to reference and track the state of the object you have reviews for in your geodata source, be it be based on OSM or some other data. The issue is simply:

your persistent id is not my persistent id.

Or perhaps better, your persistence is not my persistence. Lets illustrate that with the restaurant review example again: assume you’ve generated an id in some fashion and map that to an OSM object (more on that below), when do you consider the current restaurant different from the original, and when do you consider it different enough that you will want a new id?

Is it

And so on.

The answers to these questions depend on your use case and your business logic and a global one size fits all is very unlikely to be of any help at all. Now you might say, but there are objects, places, buildings and geographical entities that have less tendency to change, at least on a typical humans time scale and yes ids could be useful for these, but they are by their very nature easily referenced by their location4.

In summary a global persistent id decoupled from your use case doesn’t provide much utility and if you would utilize such a system it is likely that you would add a level of indirection to shield your internal business logic from being dependent on that of your id provider.

So if you are in the end creating your own ids anyway, how could you map them to OpenStreetMap entities?

Our holistic data model doesn’t make it very straight forward to continuously follow an entities modelling over its life cycle. To use the restaurant example again, it might start off as restaurant tagging on a building outline, morph to a Node5 with a location in that outline, be changed to an entrance on the outline or change to a room in the indoor mapping scheme and back again. The OSM data model doesn’t provide direct linkage between any of these, though mappers can reuse geometric elements in mapping, in the end you can’t rely on that happening in a consistent fashion. But if you can detect that such a change has happened you can use the tags (attributes) of the original element to find its current representation6.

Referencing a specific OSM object can be as simple as noting its type, its id and its version7. If the version has changed you can check the current attributes (tagging) and if they differ in a way that you consider relevant take appropriate action, which should likely always include a search for a nearby object with compatible tagging. If you find one, your id should then be mapped to the replacement. The same if the original element has been deleted. None of this is particularly difficult and you could easily use Overpass or a similar service to automatically find replacement mapping of the object you are interested in.

Enters OSMs data model curve ball: while the above works fine if your referenced object is a Node, geometry changes to linear and area features8 do not necessarily increase the objects version. This is not inherent in the data model, it is more convention than anything else, but it is a convention that is near universally observed. This means that I can move a building half way around the globe and its version will not change and for objects modelled by relations it can be even wilder.

The fix for this is simple: you need to not just store the elements_type_, its id and its version, you need to store an associated timestamp, in the simplest case the time when you retrieved the element to create the mapping9. To then check if the object has been further modified if the version hasn’t changed, retrieve the element and recursively compare your timestamp to that of the child elements10, if any of them are more recent than your timestamp, yes the object has been changed. No need to use historic data or anything exotic, the current OSM data is enough. You could even envision providing an API for this.

In summary: you don’t need Overtures GERS and you can link to OSM objects in a reasonably reliable fashion11.

This is diary post 101, I should really just shut up

essentially the proposal just defines the output format of Overtures id generation process, without providing a specification or mechanism to generate them in a compatible format. More suspicious minds than mine might come to the conclusion that Overture actually wants to start a, probably commercial, id generation service and that this is simply the initial step to entrench it before announcing. It is interesting that all of their examples are centred around conflation/de-duplication and that can only work for a third party dataset if you use a compatible method to generate the ids, aka Overtures secret sauce. Unluckily given that the Linux Foundation gave Overture a corporate structure with zero public transparency and accountability we do not know if this is something their financials could require or not. ↩

See https://community.openstreetmap.org/t/a-crowd-sourced-review-service-for-openstreetmap/ for a recent discussion on the matter. ↩

naturally the nitpicking example here is if the Gulf of America is the same thing as the Gulf of Mexico. ↩

For an overview of OSMs data model see osm.wiki/Elements ↩

Overpass permanent ids directly use such a mechanism to link to OSM elements: osm.wiki/Overpass_API/Permanent_ID. ↩

Overture bridge tables do exactly that for GERS to OSM data mapping. ↩

Linear features are modelled as Ways that contain references to Nodes that contain the actual location, moving a child Node changes its coordinates and version, but as it is only referenced by the Way object this, as a convention, doesn’t change the Way version. Areas can be modelled in 3 different way, but relevant for this discussion are really only simple polygons that are closed Ways (that is start and end Node are the same) and multi-polygons that are modelled using Relations with individual Ways either directly closed or building closed rings. ↩

How well this works depends on how stale the data is when you create the mapping, a better approach would likely be to use the timestamp of the most recent child element. ↩

For Ways this implies simply inspecting the child Nodes. For Relations this depends on the specific type, for the most relevant multi-polygons, the members are Ways and you would need to check against the Way and child Node timestamps. ↩

I didn’t address the topic of ids for streets and similar objects at all, this would seem to have even less utility than for the discussed objects and you would likely be better off by simply using linear referencing. I might expand on this is a separate posting. ↩

Today I received an invitation to attend the bi-monthly OSM US Maintainers Working Group.

But due to timezone difficulties, I don’t think I’ll be able to attend it live.

The meeting agenda has been shared, mainly focusing on the topic of standards and interoperability. There are some interesting starter questions there, so I’m intrigued to answer those questions in an OSM diary i

Today I received an invitation to attend the bi-monthly OSM US Maintainers Working Group.

But due to timezone difficulties, I don’t think I’ll be able to attend it live.

The meeting agenda has been shared, mainly focusing on the topic of standards and interoperability. There are some interesting starter questions there, so I’m intrigued to answer those questions in an OSM diary instead, hoping that I’ll be able to join the discussion asynchronously.

So, here we go :

“What standards (geospatial file or data formats, metadata schemas, wire protocols, structured text formats, encodings, etc.) does your project depend on or interact with?”

I frequently use GeoJSON format in several of my projects.

“Are there any standards that you wish would be evolved/extended but aren’t actively maintained? Or implementations that aren’t fully compliant that you wish would be?”

GeoJSON fits pretty much all of my required use cases. My only concern right now is how to make GeoJSON files more compact. I haven’t researched much about this since there’s currently no urgent performance issue that needs to be handled, but I love tweaking my apps for performance.

“Are there standard formats or protocols that you would like to use, but aren’t well supported in your language/ecosystem?”

The General Transit Feed Specification.

I’ve been interested in this data format for a long time, but I still don’t know how to properly tinker with it. Last time I worked on this, I had to make my own Python implementation to read and navigate GTFS files. I don’t know what the current situation is right now. Maybe it’s already supported, maybe not.

“What are your thoughts on Overture’s OGC proposal?”

I already posted my thoughts in a certain Slack thread somewhere. Here’s the verbatim quote:

“Does an OGC standard become legally binding worldwide or something?

I’ve been thinking for quite some time about the idea of having a single global geographic identifier for every place. Ideally, any online content that refers to a location — whether a blog post, tweet, video, or photo — would include that global GeoID so it could be reverse-searched more effectively, such as finding every piece of content that references a specific place. For now, I use OpenStreetMap node, way, or relation IDs as links whenever I mention a place as a rough workaround, but I still hope that vision could be developed further.”

“What role do you think maintainers in the OSM community should play in giving feedback on or submitting standards to formal bodies like OGC?”

I guess maintainers would only care about standards if those standards personally affect their lives (their projects depend on them).

One day, a certain still-popular web APIs were unilaterally deprecated by a certain majority market-share holder browser company. Several maintainers (me included) staged a protest on their mailing list, practically begging them not to cut our collective lifeline. A representative from that company personally told me a quick fix on how to navigate that situation, and I’ve been using that quick fix for years. I don’t know the rest of the story, but if my app is occasionally broken without a clear reason, I suspect that quick fix is no longer enough to resolve the deprecation issue. That was the last time I participated in a “standardization” discussion.

“Anything new with your project(s) you’d like to share?”

Not exactly my project per se, but several weeks ago I saw someone in an OSM diary who recommended SCEE as one of the best available OSM editors on mobile. So lately, I’ve tried doing field mapping with SCEE.

They were right, it’s so good.

But somehow preset tags are still missing (I can’t add ATM, recycling center, or power pole yet). I don’t know how to add new preset tags to the app. Is there a hidden menu somewhere, or should we make a pull request to the repository? I’m now quite interested in this topic.

Finished adding villages in Nagqu City with Tibetan names listed in the Place Names Database KNAB and having a Q-id in wikidata; I’m continuing with Ngari Prefecture.

Place names in Tibetan script are viewable using maps.wikimedia.org with lang parameter set to bo.

Finished adding villages in Nagqu City with Tibetan names listed in the Place Names Database KNAB and having a Q-id in wikidata; I’m continuing with Ngari Prefecture.

Place names in Tibetan script are viewable using maps.wikimedia.org with lang parameter set to bo.

Salut,

J’ai beaucoup édité OSM vers le milieu de l’année 2025. Maintenant, j’ai décidé de revenir!

Je vais peut-être travailler davantage sur l’Australie, et peut-être aussi sur la France, la Tchéquie, et d’autres endroits.

Salut,

J’ai beaucoup édité OSM vers le milieu de l’année 2025. Maintenant, j’ai décidé de revenir!

Je vais peut-être travailler davantage sur l’Australie, et peut-être aussi sur la France, la Tchéquie, et d’autres endroits.

Tonight I finished mapping Maud, meaning the bulk of Fairview California is mapped. There are still some places along Fairview Avenue as it goes around in a circle and becomes Hayward but this is area shared by Hayward, Castro Valley and Fairview.

It feels so good to see my home there and recognizable.

I started this project in earnest on November 18th (although I did my own stre

Tonight I finished mapping Maud, meaning the bulk of Fairview California is mapped. There are still some places along Fairview Avenue as it goes around in a circle and becomes Hayward but this is area shared by Hayward, Castro Valley and Fairview.

It feels so good to see my home there and recognizable.

I started this project in earnest on November 18th (although I did my own street back in June).

Author: Derlamaer

Date: 18 February 2026

I’m new to OSM and to cartography in general, so please excuse any imperfections in this post. As I’ve been mapping my surroundings, I noticed a gap in how we describe certain modern pedestrian crossings, and I would like to propose a way to fill it.

More an

Author: Derlamaer

Date: 18 February 2026

I’m new to OSM and to cartography in general, so please excuse any imperfections in this post. As I’ve been mapping my surroundings, I noticed a gap in how we describe certain modern pedestrian crossings, and I would like to propose a way to fill it.

More and more signal‑controlled pedestrian crossings are equipped with automatic presence detectors. These sensors detect a pedestrian (or sometimes a vehicle) and trigger the traffic signal phase without requiring a push button. This behaviour is common in newer installations, but OSM’s tagging does not yet have a clear, standard way to capture it.

This diary entry describes the situation, proposes a tag, and invites feedback.

Today, a typical signalised pedestrian crossing in OSM is tagged as:

highway=crossing

crossing=traffic_signals

To refine this, the OSM Wiki documents a couple of useful additional keys:

button_operated=yes/no Indicates whether a pedestrian must press a button to request the green signal.

traffic_signals:sound=yes/no Indicates the presence of an acoustic signal for visually impaired users. (See the wiki page for crossing=traffic_signals for details .)

However, there is no widely documented, standard key that says:

“This traffic signal is triggered automatically by a detector, with no need for a push‑button.”

That is the missing piece I am trying to address.

One concrete example can be found in Toulouse, France, where several pedestrian crossings use overhead or roadside sensors (camera, infrared, radar or similar) to detect pedestrians as they approach the kerb.

A representative location is shown on Google Street View (link as used in the forum post). In such setups:

There is no button (or the button is optional). *A presence detector starts the pedestrian phase automatically. *This strongly affects how the crossing behaves for pedestrians and vehicles, and is therefore relevant for routing, accessibility, and safety analysis.

My first thought was to introduce a simple, descriptive key:

detector_operated

Suggested values *yes – the crossing’s traffic signals are activated by an automatic presence detector. *no – there is no detector; the crossing is not automatically triggered this way (typically a button is required). Example usage:

highway=crossing

crossing=traffic_signals

button_operated=no

detector_operated=yes

This combination would explicitly describe a crossing where:

*The pedestrian does not have to press a button. *The signal phase is triggered automatically by a detector.

Explicitly capturing detector‑operated signals in OSM would bring several benefits:

Accessibility and convenience

People with reduced mobility, small children, or those pushing strollers or wheelchairs may not find it easy to reach or operate a button. Automatically triggered crossings are easier and safer to use, and routers or accessibility tools could prioritise such crossings. Better routing and user expectations

Pedestrian and multimodal routers could distinguish between: crossings that require waiting for a button press, and crossings that react automatically to presence. This can influence estimated waiting times and route attractiveness. Traffic modelling and safety analysis

Transport planners and researchers using OSM data could more accurately model: where “smart” crossings exist, how traffic phases are activated, and the potential safety benefits of detector‑based systems. Consistency with existing tags

detector_operated would sit naturally beside: button_operated= traffic_signals:sound= Together, these describe how a crossing is activated and perceived, without conflicting with current conventions.

After publishing the idea, I learned (via the Community Forum discussion) that OSM already has a key in use that represents essentially the same concept:

traffic_signals:detector

A fellow mapper pointed out that:

traffic_signals:detector is already in active use. According to Taginfo, it has values such as: yes (used >100 times) remote_sensing (dozens of uses) The key is not yet well documented on the wiki, but is clearly in real‑world use across multiple users [1]. The conclusion from that discussion was that introducing a completely new key is unnecessary. Instead, the best path forward is:

Use the existing traffic_signals:detector key. Document it properly on the wiki. Encourage consistent values to cover detector‑operated signals.

Rather than detector_operated=*, the community feedback suggests we should do this:

Basic case: generic detector

highway=crossing

crossing=traffic_signals

button_operated=no

traffic_signals:detector=yes

This tells data consumers:

There is a traffic‑signalised crossing. No button is needed (button_operated=no). A detector triggers the signals (traffic_signals:detector=yes). More specific case: remote or automatic sensing Based on current Taginfo usage, a refined value could be:

highway=crossing

crossing=traffic_signals

button_operated=no

traffic_signals:detector=remote_sensing

This expresses that:

The detector operates at a distance (camera, IR, radar, etc.), not just a simple loop or push button. Over time, the community could standardise a small, clear set of values under traffic_signals:detector=* for common detector types, such as:

yes – some form of detector is present (generic). remote_sensing – non‑contact sensor like video, infrared, or radar. induction_loop – vehicle loop detector (if needed for some installations). The key point is that the existing key can already represent “detector‑operated” behaviour without creating new, parallel tagging.

Die Strasse L170 von Göschweiler hört bei Schattenmühle auf. Diese sollte meiner Meinung nach weitergehen bis zur Strassenmündung K6516. Ich bin nicht zu 100% sicher, kann das jemand überprüfen und gegebenenfalls korrigieren.

Die Strasse L170 von Göschweiler hört bei Schattenmühle auf. Diese sollte meiner Meinung nach weitergehen bis zur Strassenmündung K6516. Ich bin nicht zu 100% sicher, kann das jemand überprüfen und gegebenenfalls korrigieren.

Une petite investigation pour évaluer l’actualité de notre carte. Voici deux cartes:

Une petite investigation pour évaluer l’actualité de notre carte. Voici deux cartes:

| Cinéma | Ecrans | Capacité | Adresse | Organisation | Web | Autres |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ciné 17 | 1 | 81 | Rue de la Corraterie 17 | proCITEL SA | cine17.ch | accès |

| Allianz Cinema | 1 | Port-Noir | SCE Suisse Sàrl | geneve.allianzcinema.ch | juillet/août | |

| Auditorium Fondation Arditi | 1 | 668 | Avenue du Mail 1 | auditorium-arditi.ch | en travaux | |

| Cinéma Arena la Praille | 9 | 1500 | La Praille, Route des Jeunes 10, Grand-Lancy | Arena Cinemas AG | arena.ch | |

| Pathé Balexert | 13 | 2909 | Centre Balexert, Avenue Louis-Casaï 27 | Pathé Romandie Sàrl | pathe.ch | accès |

| Cinéma Bio | 2 | Rue Saint-Joseph 47, Carouge GE | Fondation du Cinéma Bio | cinema-bio.ch | accès | |

| blue Cinema | 6 | 489 | Confédération Centre, Rue de la Confédération 8 | blue Entertainment AG | bluecinema.ch | accès |

| Le City | 1 | Place des Eaux-Vives 3 | Association Les Scala | les-scala.ch | accès | |

| Cinérama Empire | 1 | Rue de Carouge 72-74 | proCITEL SA | cinerama-empire.ch | accès | |

| Cinémas du Grütli | 2 | 260 | Maison du Grütli, Rue du Général-Dufour 16 | Fondation des Cinémas du Grütli | cinemas-du-grutli.ch | accès |

| Cinélux | 1 | 100 | Boulevard de Saint-Georges 8 | Association Cinélux | cinelux.ch | accès |

| Le Nord-Sud | 2 | 196 | Rue de la Servette 78 | Association Les Scala | les-scala.ch | accès |

| Les Scala | 3 | 369 | Rue des Eaux-Vives 27 | Association Les Scala | les-scala.ch | accès |

| Spoutnik | Usine, Rue de la Coulouvrenière 11 | Association Cinéma Spoutnik | spoutnik.info | accès | ||

| CinéTransat | 1 | Parc de la Perle-du-Lac | Association CinéTransat | cinetransat.ch | juillet/août accès |

Trois nouveaux:

Deux fermés:

Changement de nom:

“Temporairement” fermé pour travaux ou autre:

Comme les salles persistent souvent, on peut aussi trouver certains anciens:

En principe, il devrait y avoir:

Parfois:

Pour le cinémas open-air:

Certains ont saisi:

D’autres salles de projection et anciens cinémas pourraient certainement être rajoutés.

Entrées à vérifier/compléter:

Le contenu de la clé opening_hours devrait être normalisé ou supprimé. On pourrait se contenter de Mo-Su "30 minutes avant les séances". J’ignore quelles applications invitent les mappers de le compléter.

Les éléments suivants manquent parfois:

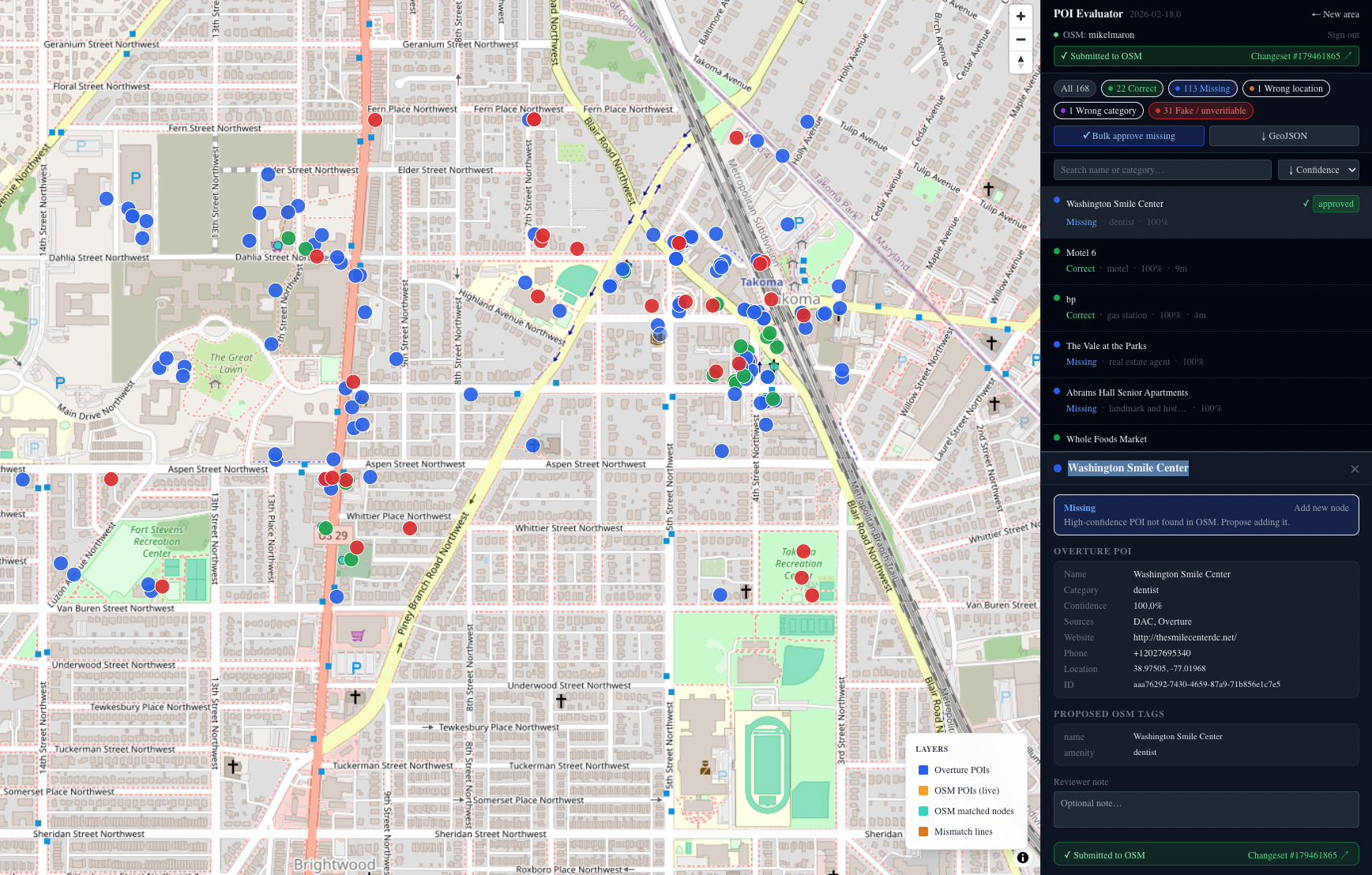

From the Build Plan developed with Claude

Project Purpose A web application enabling mappers and data quality analysts to select a geographic area, fetch Overture Maps POI data and OpenStreetMap data in parallel, algorithmically compare them, and produce two outputs: a reviewed, selective upload to OSM via OAuth2, and an annotated GeoJSON export classifying each Overture P

From the Build Plan developed with Claude

Project Purpose A web application enabling mappers and data quality analysts to select a geographic area, fetch Overture Maps POI data and OpenStreetMap data in parallel, algorithmically compare them, and produce two outputs: a reviewed, selective upload to OSM via OAuth2, and an annotated GeoJSON export classifying each Overture POI by assessment category.

No edits to OSM happen without manual review. Overture is more of an attention guide (at least that’s my hypothesis)

Lots of UX fine tuning to come. Quick observations:

I’m going to work on refining the workflow, add means to link features across Overture, ability to not just add but adjust OSM features, audit trail so it’s possible to share reviews and apply reviews against new releases….

In May 2025, the OpenStreetMap (OSM) website introduced two optional fields in public user profiles: company and location (see Github). Both fields accept unstructured free text and are not validated in any way. Since these fields are publicly visible, I wondered whether they could be useful for my “How Did You Contribute to OpenStreetMap?” (HDYC) page, particularly for identifying organized (paid) mappers. Some more background information about organized editing can be found on the OSM Wiki. According to the wiki, contributors involved in organized editing projects should be documented there and should ideally include a short description in their OSM user profile. This information is currently one of the signals used by HDYC to mark or flag potential paid editing accounts. Until now, I have relied on a semi-automated script that detects paid contributors based on text patterns found in OSM user profile descriptions. This works reasonably well for larger technology companies such as Apple, Amazon, or Meta, where contributors often mention their employer directly in their profile text. The newly introduced company and location fields therefore looked like interesting candidates for a small data quality and content analysis. The goal was to evaluate whether these fields could serve as an alternative or complementary signal to my existing semi-automated detection approach.

Data Collection and Analysis

The internally maintained OSM user profile dataset used by my services is updated daily for all contributors who have been active within the last 24 hours. For this analysis, I evaluated approximately 66,000 OSM user profiles. These profiles belong to users who:

Usage of the Company and Location Fields

A simple aggregation grouped by company and location provides an initial overview of how these fields are used. By the end of January 2026, only a relatively small number of users had filled the company field. In total, around 1,000 distinct company names were identified, although some entries likely represent spam or low-quality data. The “small numbers” here refer not to the number of companies themselves, but to the number of users associated with each company entry. Interestingly, large technology companies still appear to rely primarily on the free-text profile description rather than the dedicated company field. The location field provides slightly more interesting insights. Most users appear to enter their country name, although other formats also appear. By the end of January 2026, around 2,200 unique location values could be identified.

Conclusion

At the moment, my conclusion is that I will probably not use these fields for HDYC. The HDYC profiles currently contain, in my opinion, more reliable signals derived directly from collected and analyzed contribution data rather than from self-declared free-text profile fields. While working on HDYC improvements, I also implemented another feature that has been on my wish list for quite some time: username history. Inspired by the “Who’s That?” page, I finally implemented my own username history feature. The information is derived from the complete minutely changeset replication history. However, I am not fully satisfied with the current presentation. The feature may not work equally well for all users, especially for accounts with a long change history. I would therefore appreciate some feedback. Which option would you prefer?

If you prefer, you can also leave feedback on my OSM diary here.

In May 2025 the OSM website introduced two new optional fields in user profiles: company and location. I recently analyzed whether these fields could be useful for detecting organized (paid) editing accounts for my How Did You Contribute (HDYC) pages. Short summary:

In May 2025 the OSM website introduced two new optional fields in user profiles: company and location. I recently analyzed whether these fields could be useful for detecting organized (paid) editing accounts for my How Did You Contribute (HDYC) pages. Short summary:

Interestingly, large companies such as Apple, Amazon, or Meta still mostly appear in the profile description, not in the dedicated company field. I wrote a more detailed blog post here.

While working on this analysis I also added username history to HDYC, derived from the full changeset replication history. I am not fully happy with the current presentation and would appreciate feedback:

Until recently, I mainly used the opening_hours evaluation tool to quickly generate valid OSM opening hours. However, it often requires some manual work to simplify the syntax afterwards.

That’s why I tried using ChatGPT instead - and it works surprisingly well. You can simply copy and paste opening hours from websites, or even upload an image, and ask it to format them for the ope

Until recently, I mainly used the opening_hours evaluation tool to quickly generate valid OSM opening hours. However, it often requires some manual work to simplify the syntax afterwards.

That’s why I tried using ChatGPT instead - and it works surprisingly well. You can simply copy and paste opening hours from websites, or even upload an image, and ask it to format them for the opening_hours tag.

please format the opening hours in the attached image for the OSM 'opening_hours' tag.

Mo 13:00-18:00; Tu-Th 09:30-18:00; Fr 09:30-21:00; Sa 09:00-17:00; Su off

This is a rather simple example, but it also works well with more complex opening hours.

Immer wieder werden wir als OpenStreetMap-Community bzw. der FOSSGIS e. V. als Vertreter von OpenStreetMap in Deutschland gefragt, ob wir Schulungen zu OpenStreetMap für andere Vereine und Organisationen anbieten können. Bisher fehlten uns dafür leider die Kapazitäten – dabei liegt es natürlich in unser aller Interesse, mehr Menschen für OpenStreetMap zu begeistern und als aktiv Beitragende zu g

Immer wieder werden wir als OpenStreetMap-Community bzw. der FOSSGIS e. V. als Vertreter von OpenStreetMap in Deutschland gefragt, ob wir Schulungen zu OpenStreetMap für andere Vereine und Organisationen anbieten können. Bisher fehlten uns dafür leider die Kapazitäten – dabei liegt es natürlich in unser aller Interesse, mehr Menschen für OpenStreetMap zu begeistern und als aktiv Beitragende zu gewinnen.

Als Community wollen wir natürlich selbst bestimmen, was und wie geschult wird. Es geht nicht nur um technische Grundlagen wie den Umgang mit den OpenStreetMap-Editoren, sondern auch darum, wie unsere Community funktioniert: Wie wir gemeinsam Entscheidungen treffen, welche Daten wir erfassen wollen – und welche nicht – und wie man sich konstruktiv einbringt.

Solche Schulungen zu entwickeln und durchzuführen, ist aufwendig. Einzelne engagierte Community-Mitglieder haben das bereits getan, doch wir möchten das gerne nachhaltiger gestalten, damit es dauerhaft und in größerem Rahmen funktioniert. Deshalb haben wir letztes Jahr einen Förderantrag bei der Deutschen Stiftung für Engagement und Ehrenamt (DSEE) eingereicht – und die gute Nachricht: Der Antrag wurde bewilligt!

Bis Ende 2027 stehen uns 100.000 EUR zur Verfügung (90% davon von der Stiftung, 10% Eigenmittel des FOSSGIS e. V.), um ein nachhaltiges Schulungsangebot aufzubauen. In erster Linie werden sich die Schulungen dabei an andere ehrenamtliche Organisationen richten, zum Beispiel den Naturschutzverein, den Fahrradclub oder die freiwillige Feuerwehr. Nach Ablauf der Förderung soll sich das Angebot aus dem laufenden Betrieb tragen.

In den nächsten Wochen werden wir jetzt eine Arbeitsgruppe „OSM-Schulungen“ im Verein aufbauen, sie ist die Verbindung zur Community und sorgt dafür, dass Ideen und Prioritäten aus der Community in die Schulungsinhalte einfließen. Für die inhaltliche Koordination wird ein Auftrag an einen Freelancer vergeben. Die Hauptaufgabe liegt darin, Material zu sichten und Schulungsmodule zu entwickeln – stets in enger Abstimmung mit der Arbeitsgruppe. Und wir richten eine neue Teilzeitstelle im FOSSGIS ein, die sich um die Organisation der Schulungen kümmern soll: von der Werbung für das kommende Angebot und dem Austausch mit Organisationen, die an Schulungen interessiert sind, bis zur Durchführung der Anmeldungen und dem Schreiben von Rechnungen. Wenn möglich, soll diese Stelle auch dauerhaft nach Ende des Förderprojektes erhalten und ggf. ausgebaut werden.

Wenn Du Interesse hast, ehrenamtlich an der Arbeitsgruppe mitzuarbeiten oder Dir vorstellen kannst in Zukunft Schulungen als Freelancer oder gegen Übungsleiterpauschale zu übernehmen oder an einer der bezahlten Stellen interessiert bist, dann melde dich gerne per E-Mail an jochen.topf@openstreetmap.de.

Das Projekt wird durch die Deutsche Stiftung für Engagement und Ehrenamt über das Programm transform_D unter der Nummer DSEE-TD-1065697 gefördert.

Taking info from

www.rigacci.org/wiki/doku.php/doc/appunti/hardware/gps_logger_i_blue_747

and

www.technologyblog.de/2019/05/gps-rollover-zerstoert-gps-logger/

and

wiki.openstreetmap.org/wiki/Holux_M-241

a modified mtkbabel can set the time when reading from the device. That should probably go into some check whether it’s really a M-241 that is conn

Taking info from

https://www.rigacci.org/wiki/doku.php/doc/appunti/hardware/gps_logger_i_blue_747

and

https://www.technologyblog.de/2019/05/gps-rollover-zerstoert-gps-logger/

and

https://wiki.openstreetmap.org/wiki/Holux_M-241

a modified mtkbabel can set the time when reading from the device. That should probably go into some check whether it’s really a M-241 that is connected, but as long as the battery lasts the device shows the correct time again and logs tracks in this year and not dated 2006..

$ diff -u /usr/bin/mtkbabel ./mtkbabel

--- /usr/bin/mtkbabel 2019-10-12 12:23:29.000000000 +0200

+++ ./mtkbabel 2026-03-03 19:37:37.482923895 +0100

@@ -166,7 +166,7 @@

#-------------------------------------------------------------------------

my $debug = $LOG_WARNING; # Default loggin level.

my $port = '/dev/ttyUSB0'; # Default communication port.

-my $baudrate = 115200; # Default port speed.

+my $baudrate = 38400; # Default port speed.

my $ro_weeks = 0; # Weeks offset to fix Weeks Rollover Bug

# GPX global values.

@@ -356,6 +356,18 @@

set_data_types($model_id);

}

+# Set time to work around week rollover bug

+

+my ($sec,$min,$hour,$mday,$mon,$year) = gmtime;

+

+$year += 1900; # year is years since 1900

+$mon += 1; # month is 0-11

+

+packet_send(sprintf('PMTK335,%04d,%02d,%02d,%02d,%02d,%02d', $year, $mon, $mday, $hour, $min, $sec));

+$ret = packet_wait('PMTK001');

+printf "Set time string: $year, $mon, $mday, $hour, $min, $sec\n";

+printf "Return for setting time: $ret\n";

+

#-------------------------------------------------------------------------

# Erase memory.

#-------------------------------------------------------------------------

I have created a tag, diet:excipient_free=* , which is about finding clean supplements, i.e., without harmful ingredients that can make us infertile, inflamed, obese or even epileptic.

For example, whenever we look for magnesium (bis)glycinate, we want one thing, but many so-called “magnesium” supplements come with a lot more ingredients that might reduce the price, or enhance the appear

I have created a tag, diet:excipient_free=* , which is about finding clean supplements, i.e., without harmful ingredients that can make us infertile, inflamed, obese or even epileptic.

For example, whenever we look for magnesium (bis)glycinate, we want one thing, but many so-called “magnesium” supplements come with a lot more ingredients that might reduce the price, or enhance the appearance, but of course, at a cost; to hurt and make us need another supplement to compensate with the side effects. (Maybe they should rename those “magnesium” supplements to corn syrup supplements instead.)

Almost if not all of those ingredients fall into one category, excipients. Let’s use diet:excipient_free=* on pharmacies and nutrition supplement stores to promote a healthier future without dyes, fillers, flavorants, preservatives and other inactive ingredients that can cost us our health.

🌳 Percebendo que havia poucas informações no OpenStreetMap sobre o Parque Evaldo Cruz, em Campina Grande - PB, iniciei há uns meses o micromapeamento da área motivado pela reforma que ocorreu no local, por ser uma área verde que frequento cotidianamente e ser parte do Parque do Povo, onde acontece o Maior São João do Mundo.

♦ Identificação em campo de Handroanthus impetiginosus (Ipê-roxo-

🌳 Percebendo que havia poucas informações no OpenStreetMap sobre o Parque Evaldo Cruz, em Campina Grande - PB, iniciei há uns meses o micromapeamento da área motivado pela reforma que ocorreu no local, por ser uma área verde que frequento cotidianamente e ser parte do Parque do Povo, onde acontece o Maior São João do Mundo.

Identificação em campo de Handroanthus impetiginosus (Ipê-roxo-de-bola)

Identificação em campo de Handroanthus impetiginosus (Ipê-roxo-de-bola)

📚 Sou pesquisador da área ambiental então sempre tento mostrar o potencial que o mapeamento para o OpenStreetMap possui. Os resultados abaixo são relacionados às árvores mapeadas e identificadas no local do parque, um trabalho que iniciei faz mais de seis meses e está quase 100% pronto. Quem quiser acompanhar esses e outros mapeamentos, costumo divulgá-los no Instagram - OMapaPB.

🗺️ Esses mapas mostram as espécies de árvores que existem no parque atualmente. A identificação foi feita por chaves botânicas disponíveis na Plataforma Reflora e SiBBr, literatura da Embrapa e, principalmente, a coleção de livros sobre espécies arbóreas brasileiras e exóticas de Lorenzi.

🌲 As principais árvores encontradas são de espécies exóticas como as mungubas, algarobeiras, flamboyants e os ipês-rosa-de-el-salvador que é muitas vezes plantado como nativo por várias prefeituras.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.18810801

DOI: https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.18810801

Nesse próximo mapa, é possível verificar a quantidade de indivíduos de cada espécie, essencial para determinar a riqueza e diversidade das espécies.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.18810614

DOI: https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.18810614

O interessante de mapear o formato da copas das árvores, é que é possível renderizá-las em 3D, por exemplo no F4Map.

Renderização em 3D do Parque Evaldo Cruz pelo F4Map

Renderização em 3D do Parque Evaldo Cruz pelo F4Map

Embora mais etiquetas possam e devem ser utilizadas num inventário arbóreo (como Diâmetro a Altura do Peito - DAP, altura, fitossanidade e etc) e já existam etiquetas assim no OpenStreetMap, optei por não adicioná-las no momento.

Exemplo de etiquetas usadas no mapeamento de um indivíduo da espécie Tabebuia rosea. Abrir no OpenStreetMap

Exemplo de etiquetas usadas no mapeamento de um indivíduo da espécie Tabebuia rosea. Abrir no OpenStreetMap

🐜 Com o tempo mais informações serão adicionadas e já estou iniciando o mapeamento de outro parque urbano, o Parque da Criança. Estou muito orgulhoso do resultado e espero que incentive outras pessoas a fazerem o mesmo 🙂. É um trabalho de formiguinha que é muito prazeroso.

Gente que fecha nota dizendo que resolveu o problema, mas não resolve. Ou gente que resolve mas não fecha a nota.

Gente que fecha nota dizendo que resolveu o problema, mas não resolve. Ou gente que resolve mas não fecha a nota.